Champion of Civil Rights

Racial segregation was the law of the land during Ava’s early life. Signs designating separate spaces and facilities for “white” and “colored” were pervasive. Blacks and whites attended separate schools and churches. Movie theaters had balconies and separate entrances for black viewers. Hospitals had separate waiting rooms and wards. Blacks using public transportation had separate waiting rooms, boarded separate railroad cars, and were expected to sit in the back of the bus. They entered white-owned businesses through a back door and were not allowed to sit at a table or counter.

Ava Gardner with her close friend and personal assistant Mearene “Rene” Jordan.

Ava Gardner did not participate in public marches or protests against racial injustice, but she was not afraid to buck the absurd caste system that many of her contemporaries accepted as a normal way of life. For her, it was personal. People of color were her close friends and companions throughout her 67 years.

She described a young farm worker called Shine as “my black brother and dearest friend.” He came to help the Gardner family during tobacco season. “As far as I knew, he didn’t know who his parents were, or where they came from. He didn’t seem to know exactly how old he was, either, but he knew he was very much in this world, and he was enjoying it. He stayed in the house with us, ate with us, and was part of the family. And then one morning every fall, I’d wake up and Shine would be gone without a good-bye. I’d always feel sad at his departure.” (Ava Gardner, Ava: My Story)

Ava Gardner lived for several years with her parents, Jonas and Mollie, at the Brogden Teacherage (left) in Johnston County North Carolina.

Then, there was Virginia, the daughter of one of the maids at the Brogden teacherage where Ava’s family lived from 1925 to 1934. “I slept with her more than I slept with Mama and Daddy, or my sister Myra; blacks were like family in our house. Sometimes when Mama went into Smithfield to do the big grocery shopping on a Saturday, Virginia and I would go to the movies. She wasn’t allowed to sit downstairs, that was whites only, so I was the only little white thing, a white, blond child, up in the balcony…. I remember seeing one movie with Bing Crosby and Marion Davies…. Virginia and I came home and acted out the whole thing: one time I’d be Davies and she would be Crosby, then we’d switch around.” Ava also went to Virginia’s church. (Ava Gardner & Peter Evans, The Secret Conversations)

Just as Ava’s career began to take off, she met Mearene “Rene” Jordan, who became her maid, companion, and confidante for over 30 years. As biographer Doris Cannon points out, “In an era when the ‘N’ word was used harshly, freely and frequently and movie stars were often treated like property of the studios, the two women protected and comforted each other as sisters, had spats like sisters, and were blessed to have each other to lean on as they traveled the diverse and rocky paths of their lives.” (from the Foreword of Jordan’s book, Living With Miss G)

Throughout the many years they worked together, Mearene “Rene” Jordan and Ava Gardner traveled all over the world for filming and press tours or just for pleasure.

In 1948 Ava volunteered to work on the presidential campaign of Henry Wallace, who ran on a platform of racial equity against Harry Truman. Ava's first visit back home in two years coincided with Wallace's tumultuous campaign swing through the South. As he moved from state to state giving speeches, demanding integrated audiences wherever he spoke, he was greeted with catcalls, tomatoes, and violence. A young campaign worker was stabbed in the chest. When Wallace came to Raleigh, Ava agreed to join the candidate on the dais at a luncheon at the Sir Walter Hotel. Wallace spoke passionately of the struggle at hand against prejudice and intolerance in the South. "I know we cannot legislate love," said the Progressive Party candidate, "but we most certainly can and will legislate against hate. “Ava chatted with Wallace afterward, promising to help his campaign in any way she could. "He is a fine man," she told reporters. Her political activism was cut short, however. On her return to Hollywood, Ava was summoned to the office of Louis B. Mayer, who advised her to stay away from such “radical” engagements. "I warned Katharine Hepburn as I'm warning you, and she wouldn't listen to me,” he was quoted saying, “and look at her, she's destroyed her career!“ (Lee Server, Ava Gardner: Love Is Nothing)

Ava Gardner pictured at an event in the 1980s with two of her dearest friends – actress, singer, and activist Lena Horne (left) and former First Lady of Pakistan Begum Nahid Iskander Mirza (right).

Ava became Lena Horne’s neighbor after buying a house at Nichols Canyon near LA in the late 1940s. They remained close friends for life even after Ava was chosen for the role of Julie LaVerne—a part that Lena wanted—in MGM’s version of the musical Show Boat in 1951. When Ava died in 1990, Lena was one of only two stars who sent flowers to the funeral in Smithfield.

Ava retained her U.S. citizenship while living in Europe and stayed abreast of developments in the American Civil Rights movement. In 1969 Ava and Bill Cosby co-chaired a soul food dinner at the Waldorf Hotel in New York City. It was a fundraiser for the Free Southern Theater, a group who worked to “make theater available, useful, and relevant to the lives of the people in poor, black communities of the rural and urban South.” Guests paid $100 per plate for fried chicken, collard greens, black-eyed peas, and cornbread. The event raised $50,000 for the organization.

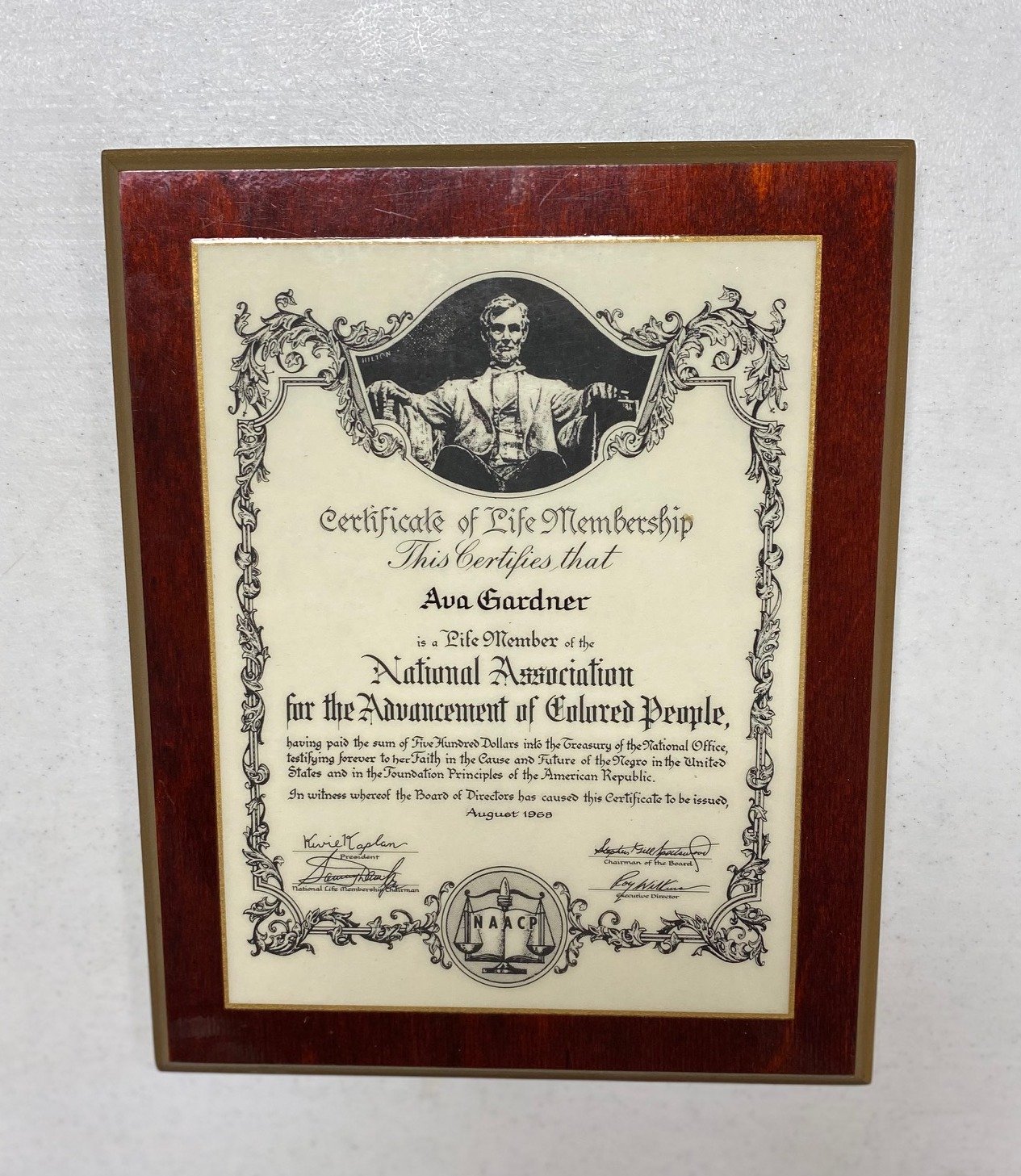

(Left) Ava Gardner with friends Lena Horne and orchestra leader, composer, musician Duke Ellington at the dinner in support of the Free Southern Theater. Ava co-chaired the fundraiser and both Lena and Duke performed at the event. (Right) Ava Gardner’s membership certificate for the NAACP, part of the Ava Gardner Museum’s permanent collection.

Moved by the senseless killing of Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., she sent a $500 gift to the NAACP and in August 1968 became a Life Member, “testifying forever,” her membership certificate reads, “to her Faith in the Cause and Future of the Negro in the United States and in the Foundation Principles of the American Republic.” This certificate is now on display in the Ava Gardner Museum in Smithfield, North Carolina, where her civil disobedience, unbeknownst to her at the time, began in the balcony of a segregated movie theater.